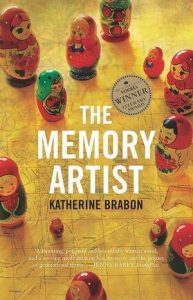

Katherine Brabon’s The Memory Artist, which won The Australian/Vogel Literary Award for debut novelist for 2016, is the story of Pasha Ivanov who grew up in the 1960s in the small Moscow apartment where his dissident parents and their friends gathered. They were determined to find out and circulate information about the Stalin government’s ruthless repression, perpetuated by subsequent regimes, long after his death. Tens of millions had been murdered, exiled to brutal remote gulags, placed in mental institutions or, simply disappeared. Control over information, even thought, brutally enforced. Fear as powerful a censor as a prison cell or a man with a gun.

Katherine Brabon’s The Memory Artist, which won The Australian/Vogel Literary Award for debut novelist for 2016, is the story of Pasha Ivanov who grew up in the 1960s in the small Moscow apartment where his dissident parents and their friends gathered. They were determined to find out and circulate information about the Stalin government’s ruthless repression, perpetuated by subsequent regimes, long after his death. Tens of millions had been murdered, exiled to brutal remote gulags, placed in mental institutions or, simply disappeared. Control over information, even thought, brutally enforced. Fear as powerful a censor as a prison cell or a man with a gun.

In the 1980s, following Brezhnev’s death, new leader Mikhail Gorbachev has ushered in fledgling glasnost, an increased openess about the activities of government institutions. Pasha is in his early 20s and wants to write a book about all the stories, of the killings and oppression, he heard while growing up. To make art from what had happened. In particular he is haunted by the situation of those forced to undergo “treatment” in the mental institutions, both as a punishment and as a pre-emptive measure. While many Russians wanted to erase that period from the personal and collective consciousness, Pasha believes that only by openly recognising what happened in their past, can they exist truthfully in the present.

“How the state and citizens alike acted toward history would determine how anyone cared, or not, about people in the future. But it would not always be the case … over time the impact would fade … then what we went through would simply become events; it would become something that happened to some people long ago.”

By the 1990s the Soviet Union has disintegrated, morphing into the Russian Federation. Pasha is leading a lethargic existence in St Petersburg, teaching Russian to foreigners, his book unwritten. He is still overwhelmed by the need to recover the past (including the death of his father), but is beginning to believe he is striving for something he can’t quite grasp and possibly never will.

Like many novels that move between time periods, it’s not always a seamless leap back and forth. But Brabon takes us on a fascinating (if at times particularly slow) journey through Russia from the cramped brutalist apartment buildings in St Petersburg to Moscow’s Pushkin Square with the arrival of McDonald’s attracting queues longer than the lines to see Lenin’s mausaleum; a remote country dacha during the eternal daylight of summer and an abandoned gulag in one of the remotest part of the country, icy and windswept, with its thousands of ghosts. Through exchanges with characters like Oleg, the dissident friend of his parents, meticulously creating what he sees as the real map of Russia by marking in all the sites of all the prison camps.

There’s no neat ending to The Memory Artist. No lightning bolt of understanding for Pasha. Braborn is teasing out the issue whether it is possible to ever totally understand the enormity of such a traumatic past. And whether the attempt to retrieve memory, even if not always successful, is enough.

The Memory Artist draws on Brabon’s extensive academic work, notably her Masters in Modern History, and was written as part of her PhD. When asked recently why she had decided to move from acadmic writing to novels Brabon said she “never felt like I was any good at academic writing (with fiction) … I was finally able to express myself in the way I wanted.”

Australia’s Vogel Literary Prize has been the launching pad for some of the country’s most acclaimed authors such as Tim Winton, Gillian Mears and Kate Grenville. To judge by The Memory Artist, Katherine Brabon is on track to join that company.

The Memory Artist is published by Allen and Unwin.

Comments are closed.